Some of my suggestions in this chapter also apply to sales presentations, elaborated further in a separate chapter. Refer to both, for a complete preparation towards a sales presentation.

Bond. Presenter Bond

When you take the stage and start talking, your audience may not yet be ready to focus on your story. As they collect their attention onto you, they’ll have to first get used to you and place you within their mindsets.

Even the minutest things can hinder and distract them at this stage, consuming their attention. For example, your accent. In many of my presentations, I begin by mentioning that I am from Holland, relieving my audience from the common “Where is he from?” debate. In smaller groups, some smalltalk preceding the business session can take care of this basic introductory necessity.

What do you do?

Also, while entrepreneurs live and breathe their companies 24/7, investors only just arrived on the set, and perhaps all they know is the company name. As you begin your presentation, investors’ attention will be offset until you cater to their knowledge gap. Make sure they gain a basic understanding of what it is that you are going to discuss before diving into the heart of the matter.

Briefly tell your audience what your idea is simply by classifying your company. When you say “We are a Facebook for golf enthusiasts, sort of,” your audience can then sit back and glide into listening mode, focused on the rest of your story, even if the classification is not 100% accurate. As you proceed in telling them your story, pinpoint its essence more accurately.

In between the lines

SIZING YOU UP

One of the most important criteria for investors in evaluating a potential business is you, the entrepreneur, the presenter. How they perceive you, as a person, at this elementary stage, is vital.

Your slideshow provides information about your company, but they can also find this in your business plan and/or website. Investors can read about you in your CV. When they come to the pitch they want to sense the pulse, and will attempt to figure you out, projecting their feeling onto your company as a whole. Unlike factual information that can be found elsewhere, the impression of you as a person can only be conveyed in a live presentation.

The information you present constitutes half of the charade, it is you and the mark you make as a person that completes the picture.

Are you trustworthy? Investors will be musing on how it’ll be to work with you as a Board member, and if you can be trusted at all.

Trust and integrity are the most important personal traits investors seek, and they search for these in you as you unfold your story. You can’t very well flash a slide declaring “I never lie.” They need other indications that point at this from between the lines.

For example, they could ask you questions for which they might know the answer. If you do not know or are unsure, just say so, never make something up.

Another indicator: do you tend to gossip, or leak information even though you just met them a mere half hour ago? If you do this to your potential investors, it is highly likely that you will display the same behavior with other people.

There is never an absolute upside in bending the truth. Although pitches are not well suited for extracting inaccuracies, investors will drill down later and eventually uncover things in the subsequent due diligence process.

By that time you may have very few options left. Having spent more funds, you desperately need the new investment. But because inaccuracies were detected, your one and only investor candidate bailed out at the very end of the process. You’l find yourself in a predicament. Firstly, because it takes time to start the process with another investor, and secondly, finding this investor might be very hard as you’ll be asked to explain why previous ones pulled out. So, don’t risk trust just to paint a brighter picture at your pitch. Your art will best shine in light of your candidness.

What’s it like to work with you? If you interpret an investor’s question or feedback as a major assault on your company, fighting it back relentlessly, investors will mark you as very strong willed and determined. But, on the other hand, you may come across as someone not open to constructive feedback from Board members, causing you to lose credit with investors.

Remember your behavior tells much of your story, so chose your reaction wisely. Admit you do not know, acknowledge certain suggestions as useful, or, if you disagree, come up with a constructive argument.

How do you treat your colleagues? If your team is also present with you in the pitch, investors will scrutinize you on the way you manage and lead. Be a respectful team player, and allow your team to also take part while you maintain the gravity.

What should be covered in an investor pitch?

The basic pitch ingredients

I believe no standard template can suffice for all investor presentations. Every company is unique, and investors differ in expectations and worldview. There are some topics expected to be covered in pitches, and you can adjust the relative weight and order in which to present these in your specific case. Use your instincts and common sense.

- Bond: start with a very basic description of what you do, to help investors focus on your presentation.

- Introduce: briefly familiarize your audience with you and your team (full CVs can be added as appendix for further information.) If relevant, elaborate a little on how the team has worked together in the past, or other ways you have collaborated with each other.

- Pinpoint need: engage your viewers by clearly spelling-out to them the big issue you are about to solve, the essential need. Use different angles to do so. Create a case example, or a small story to highlight the experience of just one customer struggling. Use quantitative data to show how the cost structure of existing products can be dramatically undercut. It is important to cover both the cold analytical side of the need, as well as the emotional aspects. Make the investor feel the pain.

- Offer solution: this part should be a natural extension to your pinpointing the need. Spend more time in showcasing the problem, because there is no better way to sell your solution to investors (and customers) than selling them the problem. The detailed features of your product can wait for subsequent meetings.

- Scope the market: it is not enough to scope the size of your market with a top-down “$1B market” quote from a market research report (IDC, Gartner, etc.) To ground it, explain how you can arrive at that value. While people might not agree completely with the overall point estimate, your calculation indicates the thought process by which the market size can be estimated, how to think about the market. It enables investors to run the calculation themselves, maybe with slightly modified assumptions.

- Showcase the technology: explain your technology or product at a level basic enough for grasping, yet detailed enough to indicate uniqueness. Balance simplicity and complexity, because as you do not want to offend your audience by implying they’ll never comprehended your technology, you must also reassure them that your technology is unique and hard to replicate. One option to achieve the latter is to dive in really deep into one aspect of your technology, explain it fully to the investors. In this way, they get a sense of how smart your solution is, without having to go through the entire technology architecture.

- Map the competition: every business has competitors and there are always alternatives. Saying you have none shows you are too naive to run a business. Plot yourself on a 2x2 map, or position yourself in a simple feature table to show how you differ from others in the market. If your company has little differentiation and it is all about fast execution, just be honest and say so. In that case, emphasize the strength and track record of your team. An experienced team with a superior ability to execute can never the less be an interesting investment opportunity.

- Making money: explain your business model, and give a credible analysis of how you can get your revenues and profit target within 5 years. See the section about business models later in this chapter.

- Spend wisely: long-term financial projections are uncertain, while short-term cash outlays are very predictable. Elaborate on your company’s financial plan in respect to its funding. Define clear, realistic milestones, show you have thought things through. Your projections in the short term (highly certain costs, highly uncertain revenues) should be very precise and detailed. Your projections 5 years out should be high level and ball park.

Investors do not usually follow a predictable, logical story structure

The investor mindset

You’ll find investors tend to think outside your nicely organized agenda page. They have big questions and smaller questions, and they’ll want them all answered, with focus on the big ones first.

Sometimes the big question can be so apparently huge and noticeable, they hang in the air and requires your immediate attention. Examples for such elephants in the room, are very strong competitors that may exist in your market, or the fact that your CEO is... Really? Only 21 years old?

It’s not wise to start a presentation by openly brushing off competition or dodging the obvious reality of your management’s age and experience. Rather, you’ll find it is helpful to get such issues out of the way early on. Once you clear the air, investors can take in the rest of your presentation relieved of the weight of worrying facts.

If your story is not completely aligned with the investors’ mindset, they are likely to interrupt you with questions. I think that in a relatively small meeting, this shouldn’t pose a problem, and you can easily deviate from your original story to take the time to answer, or reroute yourself accordingly along your storyline. Don’t risk killing the dialogue by saying they’ll find answers later in the presentation, 25 slides away. If you are completely on top of your material you should be able to improvise and provide an answer at any given moment. In presentations with large audiences it is harder to answer every time a question comes up.

Prepare for your meeting

Do your homework

It pays off to invest time in preparing for your investor presentations. Research which investors best fit your company? Where’s your best access point?

Most venture capitalist’s websites clearly state their investment criteria. If there is no match, there’s little point in approaching them for an investment. If there is a good fit though, it is worth adjusting your deck specifically to each investor. Show how your company can contribute to the portfolio of companies, how your startup can benefit from the expertise in partnering with this firm. Go through a VC portfolio of companies and understand the basics about them before you decide to approach the VC fund.

Use LinkedIn to research the personal background of a potential investor you targeted. Try to find a common background, such as school, university, graduating major, etc. This helps in positioning your pitch better and creating a stronger bond with the investor.

Many VCs maintain a blog, either as part of the firm they work for, or under a personal title. These blogs are a goldmine of information about their preferences and approach. Mark Suster for example, gives an extensive debrief of his decision-making process after making an investment. It is so detailed you can almost mistake the blog for the minutes taken at the investment committee meeting itself. Fred Wilson is another good resource to add to your daily reading list. Always come to an investor meeting well prepared.

Different occasion, different pitch

Different pitches

There are different types of investor meetings and each type of meeting requires a different type of deck, if at all.

2 minute elevator pitch: if you casually bump into someone to which you want to pitch, just focus on raising enough interest to justify a followup call. This is all you should expect, not landing the investment. Marketing guru Seth Godin always reminds us that “nobody has ever bought something in an elevator.”

Also, the 2 minute elevator pitch gives you ample time for dialogue, so watch for facial expressions and pause if a question comes up. It is better to address concerns head on, even in this type of short pitch, instead of firing a continuous stream of facts that will be stalled by a friendly handshake or wave of goodbye, without room for a followup call.

Why experts are so bad at explaining things: the Curse of Knowledge

Keep in mind it is very hard for an expert to explain their area of expertise comprehensively, especially to a total outsider. It’s just one of the symptoms of the Curse of Knowledge, as the Heath brothers explain in their book Made to Stick. I like the analogy they use: As I tap a piece of music on a table, I form the whole piece in my head, where it comes to life in its entirety. I hear the orchestra, envision the conductor, and, of course, my tapping is in perfect sync. For someone else, it’s just tapping, stripped of the entire context played out only in my head.

The use of fluffy language and buzzwords are symptoms of the Curse of Knowledge too. While these form a clear understanding in the mind the person saying them (the expert), other people remain oblivious to their meaning. For example, if you sum up your product’s essence as “our solution is scalable,” you sound very much in tune with what virtually every other company is saying about their own products. Your comment remains devoid of any real meaning.

A short statement is required for an elevator pitch, but not one that’s not specific enough. As the corporate cliche phrases it: a boiler plate can sometimes be so hot, to the point there’s no water left.

Many elevator pitches get diluted this way, with nobody really understanding them outside the person who tried to pitch. “Our company has a scaleable solution for a huge problem in a large market where our excellent team is able to generate very high margins.” You may have encapsulated everything, but such a message renders no meaning to your listener, the other person in the elevator.

A good elevator pitch is hard to craft, just like any grabbing slogan (for example Apple’s “one thousand songs in your pocket”.) For good examples of startup one lines visit the funding web site AngelList. You will see that many 1-liners, use analogies, and are free of fluffy buzzwords.

Mission and vision statements are other examples of the Curse of Knowledge. To the insider who sat through all the vision statement workshops and remembers all the deliberations, such paragraphs may sum up everything the company stands for. To the outsider, it sounds like a random string of buzzwords generated by an automated algorithm. I am not a big believer in opening your story with a mission or vision statement.

A print out deck in a coffee chat: pull out the pages you need

The 30 minute one-on-one: if you manage to get a longer meeting with a potential investor, over coffee perhaps, keep smalltalk to a minimum (besides establishing common grounds.) Investors are much more interested in finding out about your company than today’s weather.

Take your deck with you, but prepare for a relatively random meeting where you only pull out a slide if needed, perhaps the map showing competitors, or the detailed financial projection. In short pitches such as these, your story should be told directly as part of your conversation, not as a presentation session.

The iPad can be a great device to pull out random slides as you talk. Or, you can use printouts and scribble and draw on them to elaborate freely on your idea, as you go along. Remember the objective of the coffee chat is not to get the investment, but to secure the next stage in the due diligence process.

The standup presentation: an extended pitch in front of investors, resembling a classic live presentation. Remember its as much about what you convey to the audience as a person, as it is about the actual content of your slides.

Ideally you want a specific deck for each presentation, although I do admit it’s not always practical to have a big slide bank from which to pull slides for the coffee chat (think about which ones to pull), and a full deck for the standup presentation.

Also have a deck ready for emailing off to investors ahead of time, if needed, add bits of text where otherwise your verbal explanations would have sufficed. This “teaser deck” does not need to contain the full detail about your financials and technology yet.

Instead of a slide deck, people tend to email a so called Executive Summary ahead of the actual presentation. I am less in favor of such wordy investor documents, because, for investors, skimming through 30 nicely designed and highly visual slides is better than reading a dense one pager, sentence by sentence, paragraph by paragraph. Chances are the investor picks up less from the one pager. People tend to grasp quicker as they look at pictures rather than from reading text.

A napkin explaining business

Most investor pitches I see claim year five revenues of $50M to $100M. Flashing just this piece of information is not going to convince investors. An incredibly complicated Excel sheet won’t get you there either.

What you need to show to make your facts believable is why you’re going to hit that mark. Neither the bottom line number or the detailed model can do this for you. What you’ll need is the Napkin calculation.

A napkin calculation is simple, but it requires preparation to get it right. When modeling the company economics, I usually go through a cycle. I start off with a very simple calculation that gets me to a ballpark answer, easy to follow and verifiable (in calculation at least.) Next, I go into incredible detail using an Excel model, adding all the complexities and offshoots while constantly monitoring myself to avoid deviating from the ballpark (where deviation occurs, in 90% of the cases it’s due to a calculation error, but in 10% it expresses a new and unexpected insight.)

After the detailed economical model is finished, rock solid and bug free, it is time to simplify everything back to the higher level, initial, ballpark number. Simplification is not easy. You need to pick those drivers in your business that are most important, decide which factors should show and which to hide.

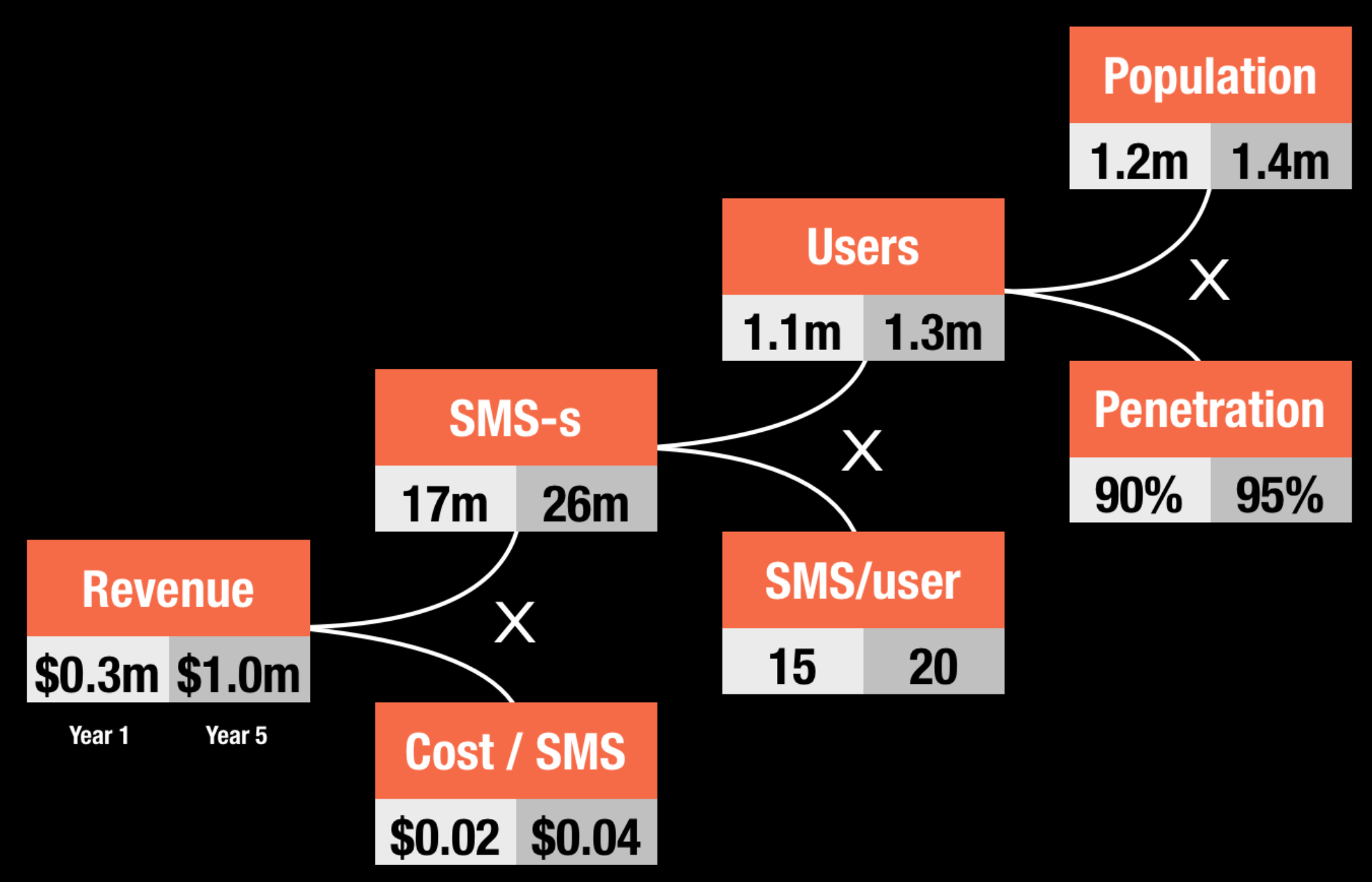

Numbers that people can relate to

The best economical drivers to pick for your napkin calculation are usually the ones easily imagined in real life. For example, the number of SMS messages sent per month is tangible only to telco experts, able to put it in context in their minds because they are proficient in such topics. The number of SMS messages per user per month, is something everyone can relate to.

With all this preparation, you are now able to let your potential investors write their own ballpark or napkin calculation of the company potential.

Provide them with the basic framework, the six numbers you need to multiply to get to your $75M estimation in year five. Investors may not agree with all six numbers, but at least you provided the framework by which to apply their own estimates. Getting the point estimate right is not important, as much as agreeing on the order of magnitude and how to get there.

To visualize my napkin, I often use a tree as shown here. Use rounded, simple numbers that calculate across the screen. If you are pitching live, you can also make calculation on a whiteboard, but be well prepared to pull numbers accurately from memory.

There is also psychology involved here. Your numbers are likely to be outrageous. Are you able to defend them realistically? Are you open to input that can challenge your numbers? Of course, investors discuss financials with you as another means by which to figure you out personally, evaluating you as a potential CEO of a portfolio company. Do you come across like a sane and realistic person to work with on a daily basis?

It’s clear your forecasts are made up, and their credibility will fade against a skilled analyst’s prediction of IBM’s next quarter’s earnings. The latter is easier to arrive at, by the way. Still, your credibility does not lie in the accuracy of your estimation as much as in it is in your consistency of data. Applying two different sales numbers on two different pages will raise a red flag with investors, indicating to them that you are not on top of things. A footnote saying the number on page 34 includes VAT and the number on page 22 does not will not smooth things out for you.

Don't get into a discussion whether you added up correctly

The same logic applies for calculations. If investors feel they need to check you up on your math, this is what they’ll be busy doing on every slide, and their attention will be lost to this. So, check and then recheck again. When the final version of the presentation is ready, take out the calculator and review every page carefully, by hand, even if you copied data straight from Excel. Look for typos, or any odd rounding errors and correct them manually directly on the slides.

You probably noticed that we haven’t discussed data derived from market research agencies, often used to support financial forecasts. I consider these a data point, but not the most important input for a business plan. Almost all markets discussed by IDC or Gartner are a $billion, and most of the time are far too broad in scope for any new startup. The useful thing about such forecasts, is they provide a good categorization for technology markets. So, you can say “We are in the so and so business.” But, and I have seen it happen, you run the risk of a VC not being able to place your startup in any IDC box, and this in turn makes it more difficult to explain what it is you do.

Murphy's Law will strike

The live demo

If you are in the high tech sector you face the challenge of also giving a live demo of your product during a pitch. If the meeting is a short one (an hour or less), my advice is not to show your product live, but use a series of carefully planned screen shots instead, simulating its operation in pictures.

Murphy’s law ensures with all certainty that whatever can go wrong, will go wrong. And from my experience, this is particularly true for live high tech demos. There are just so many variables that can falter: Internet connectivity, screens, the application itself. If you are in the middle of a short pitch, such disruption will pop the momentum. Ideally you want your pitch to be a focused burst of energy, motivating your audience, leaving them to crave for more. Stalling for a WiFi password does not help this.

Another problem with demos, is that some functionality is redundant and uninteresting to viewers, for example, logging in, creating profiles, entering data. These do not constitute the clever features with which you planned to sweep investors of their feet. Also, a live computer screen is more often than not totally illegible as an overhead projector, especially with fonts smaller than 12 points.

So, prepare an interesting story instead, set it up beforehand in your application, take lots of screenshots and paste them in the right order in your presentation. Zoom in, to show interesting aspects of the screen, crop out window bars, ads, and other fluff you don’t need showing. Circle what people should be looking at. Add brief explanations in text boxes where needed. This should serve as a demo, one that cannot go wrong, high–paced, legible, and focused on the important elements you want the audience to see.

Still, it can be useful to bring your application along too, but not to showcase as a live demo. Bring it in to make it tangible to the investors, as in “Here it is.” After you delivered your 20 minute pitch flawlessly, people will be interested, and you can then suggest a second, longer session, dedicated to a live demo.

Not everyone in your audience has an engineering degree, or will they be able to understand the ins and outs of your product. Be prepared to explain basic ideas behind the complicated technology, at a level suitable for any audience at a reasonable level of intelligence, not necessarily a professional one. Refrain from saying “This is probably too hard to grasp,” because it’s offensive. Keep in mind Einstein’s insight, that if you’re unable to explain something to a six year old, you probably don’t understand it yourself either.

QUICK SUM UP

Best prepare for an investors meeting by anticipating their concerns, and create an intelligent dialogue around this. One more thing: a good night’s sleep before this important meeting is probably the most important way to prepare.